Intro to Farmscaping: Insectary, Trap, & Repellent Crops for Pest Management

By Jon Ault, Johnny's Assistant Farm Manager

Farmscaping is a whole-farm approach to biological control of pests. It involves managing pests sustainably through cultural practices such as insectary plantings, trap cropping, and cover cropping. These practices are designed to support beneficial insects while discouraging pests; the goals are to: reduce pest counts below damage thresholds; reduce or eliminate the need for chemical insecticide applications; and improve yields.

What Are Beneficial Insects?

Beneficial insects are the natural enemies of target pests. Think of them as living insecticides! Although you can purchase beneficial insects for targeted application, this article will focus on attracting and supporting beneficials already existing in your local area. Many are local and ready to help!

Common beneficial insects can be found across a range of insect taxonomy and ecosystems and include: ladybugs, big eyed bugs, spined soldier bugs, assassin bugs, minute pirate bugs, carabid beetles, soldier beetles, hoverflies, green lacewings, predatory wasps, and even spiders. Parasitoids such as parasitic flies, parasitic wasps, and parasitic nematodes are also important to consider.

Lady beetles are beneficial predators that feed on aphids and other soft-bodied pests. Image courtesy University of Maine Pollination Security Project

Beneficials can be broadly categorized into two groups:

- Predators: large-sized generalist feeders which typically prey on insects at both immature and/or adult life stages. They tend to be larger, slower, and quite varied in their diet, including sometimes even eating each other when their preferred food is absent!

- Parasitoids: small-sized specialists—typically wasps or flies—that target different life stages of their prey for attack, such as eggs and larva, but rarely adults. Given their small size, parasitoids can be very hard to observe in the field and their importance may not always be apparent until after they have left a field. Parasitoids are especially effective killers of usually very specific pests and are highly susceptible to both habitat modification as well as pesticidal sprays.

The braconid wasp is an important parasite of the tobacco and tomato hornworms. Image courtesy of R.J. Reynolds Tobacco Company, Bugwood.org

A few examples…

- Lady beetle larvae consume 100–400 aphids during their development (around 23 aphids per day).

- The parasitoid braconid wasp, Cotesia congregates, injects its eggs into the living body of both tobacco and tomato hornworms. The eggs hatch, and the wasp larvae consume the bodily fluids of the hornworm, eventually emerging through the pest, pupating, and leaving the caterpillar to its death.

- Ground beetles in the family Carabidae consume weed seeds, in some cases decreasing weed pressure in the following year by 80–90%! Ground beetles are also opportunistic predators of many pests, including aphids, cutworms, armyworms, and cucumber beetles, among others.

Ground beetles are prodigious weed seed consumers. Image courtesy Eric Gallandt, PhD, University of Maine Weed Ecologist

Vertebrates (birds, bats, reptiles, etc.) can also be beneficial in the right circumstances. There are many potential allies in the environment that a grower can enlist against pests!

Why use beneficials?

Use of beneficial insects can help make the growing operation more environmentally sustainable by achieving pest control through means other than chemical intervention. Plus, real cost savings can result from this integrated approach. Finally, farm employees appreciate improved safety associated with less chemical exposure.

Attracting Beneficials and Discouraging Pests

A good farmscape plan involves implementing strategies designed both to attract beneficials and hinder pests. For example:

- Habitat modification: growing plants that provide beneficial insect habitat, including access to shelter, nectar, and alternative prey. These plants, called insectary plants, serve to attract and retain beneficial insects, and grow their numbers.

- Cultural Practices: that disrupt, discourage, antagonize, repel, and trap pests, such as crop rotation and targeted sprays are important in breaking the pest life cycle and supporting local beneficials. Repellent plants can also be helpful in discouraging pests. Finally, use of trap crops pulls pests away from cash crops by exploiting their feeding preferences.

Let’s look at each of these elements in turn, using some examples from the Johnny’s Research Farm.

Getting Started

It may be helpful to start with a focus on a single crop where you are experiencing high pest pressure. At Johnny’s, we began with our cucurbit crops. We were experiencing heavy pest pressure from cucumber beetles, squash bugs, and green peach aphids, which in turn were spreading disease within the crop.

Start by asking yourself the following questions:

- What crop do you want to protect?

- What are the key pests attacking this crop?

- What beneficials do we need to attract to target that pest?

- How do we attract those beneficials?

To answer these questions will take some research. Here are some resources that we recommend:

- ATTRA Trapcropping Resources

- UMass Amherst Scouting Resources

- Ecological engineering for pest management

- Cornell University IPM guides

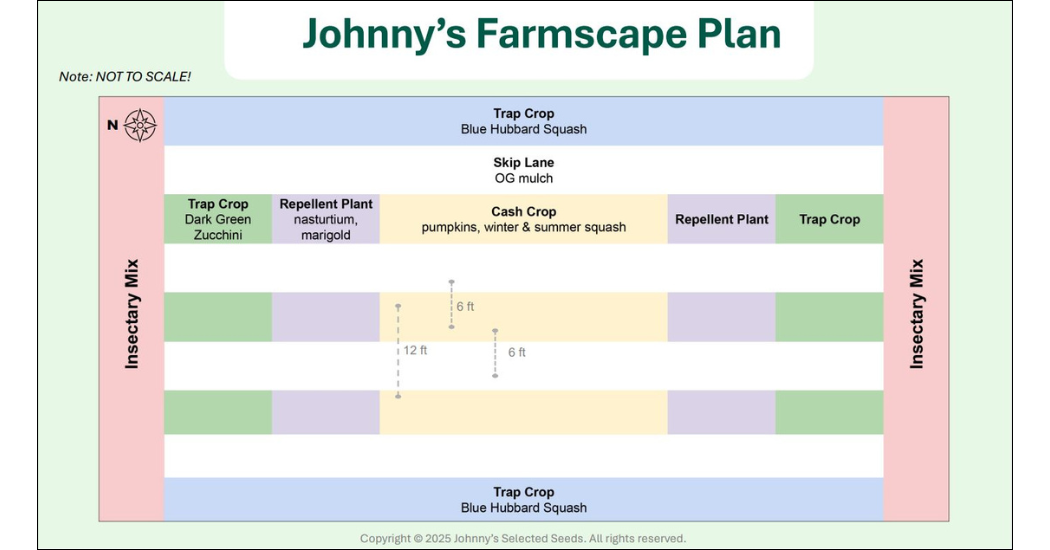

Implementation at Johnny’s

At the Johnny’s Research Farm, we implemented several elements into our farmscape plan. These include insectary plantings, trap crops, repellent crops, and skip lanes (unplanted/mulched rows). We also changed our use of organic insecticides, spraying the trap crop only when pest pressure met an established threshold, rather than spraying based on the calendar. Finally, we protected the cash crop with row cover.

Insectary Plants, Trap Crops, & Repellent Crops

Insectary Plants

Beneficial insects need food and shelter. An insectary planting will greatly increase the likelihood that beneficials will hang around and help out with pest management.

Johnny's "Bug Blend"

At the Johnny’s Research Farm, we lovingly call the crops that we incorporate into our insectary, our “Bug Blend.” This combination of crops has a prolonged and overlapping bloom time and includes: Oats, Buckwheat, Phacelia, Alyssum, Dill, Cilantro, Crimson Clover, Medium Red Clover, Berseem Clover, and Ammi.A mix of insectary crops provides a diversity of services to the native insect population. For example, buckwheat is especially beneficial because it flowers over a long period of time. Grasses and grains provide refuge for ground beetles and spiders, and a shady place to lay eggs for other beneficial species. Plants in the Apiaceae, or the carrot family, like cilantro, dill, and Ammi, produce umbels of tiny, aromatic flowers that are a good source of nectar.

Trap Crops

Trap cropping is a strategy that pulls pests away from cash crops by exploiting their feeding preferences. In other words, the target pest is diverted from the cash crop when it encounters the delicious trap crop. In our cucurbit example, we placed trap crops of Hubbard squash on the perimeter of the field and trap crops of green zucchini on the ends of rows. Ideally, the trap crop helps to limit or eliminate the need to spray the cash crop. We spray the trap crops only when/if pest levels on trap crops reach a target level. More information on action threshold levels for chemical intervention can be found either in the New England Vegetable Management Guide or Cornell’s crop specific IPM guides.

Repellent Crops

We use plantings of nasturtium and marigold to repel pests from cash crops.

Skip Lanes

We also use “skip lanes” (unplanted, mulched rows) to buffer the cash crop and deter the movement of pests.

Results at Johnny’s

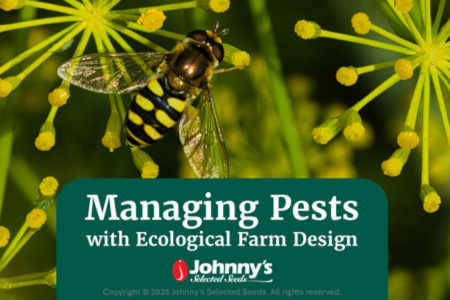

Hover flies are ardent consumers of aphids in their larval stage, and nectar-feeding as adults.

Our initial results from implementing these strategies in two fields totaling about 6 acres of cucurbits included:

- Total pesticide treated area decreased by 97%

- We nearly eliminated expenditure on insecticide spray

We saw a huge hoverfly population, very large ladybeetle population of various types, large numbers of minute pirate bugs, and evidence of parasitized squash bugs.

Parasitized squash bugs. The white eggs on the backs of these squash bugs are likely from Trichopoda pennipes, a predatory fly. Image courtesy Whitney Cranshaw, Colorado State University, Bugwood.org

Lessons

Here are some lessons learned from our research and our implementation efforts:

- Targeted plant selection is better than random plant selection. Your insectary mix needs to provide shelter and food to your target beneficial insects both in the right quantity and at the right time. Your trap crop needs to be attractive enough to your target pest to be useful. In other words, it pays to do your research on which plants will best fit your needs.

- How does incorporation of these plants affect your land preparation? Plan ahead to understand how your farmscape plan will change your farm operations as a whole.

- Be intentional about data collection. We highly recommend the UMass Amherst Scouting Resources.

5 Steps to Establishing an Insectary

The steps outlined below are adapted from a University of Maine Cooperative Extension Fact Sheet coauthored by Eric Venturini, former Education Coordinator here at Johnny's.

Minimize Weed Pressure

The first step to successful establishment of insectary mixes is the control of weeds, especially weed seeds. A properly prepared seed bed sown to a perennial mixture of flowering plants can continue to provide beneficial insects with forage for 5–10 years only if weed pressure is minimized. In fact, if weeds are not controlled prior to planting, they can and will out-compete the slow-growing perennial flowers within the first year.

Methods that growers can use to drastically reduce the weed seed bank include stale-seed bedding, flame-weeding, soil solarization, topsoil removal, a combination of cover-cropping and stale-seed bedding, or, if necessary, judicious repeat applications of herbicides. Even two or three cycles of stale-seed bedding in the spring prior to sowing a flower mix can greatly reduce weed competition and help to increase the longevity of the planting. See our article on Weed Management Basics to learn more.

Prep the Soil

We do suggest doing a soil test (available from your nearest agriculture university) and following recommendations in the results. Light shallow tillage to break up the soil structure prior to sowing seed will help increase germination and emergence.

Sow the Seed

Native seed drills, hydro-seeders, and spin seeders like the Ev-n-Spred® are all effective tools for seeding beneficial insect mixes. Except in extremely large areas, the Ev-n-Spred Seeder is a practical option that can be easily used to seed plantings of up to several acres.

Very small seed, such as wildflower seeds, should be bulked with sand, vermiculite, or something similar to help ensure that the seed is distributed evenly throughout the planted area. After sowing, lightly rake the area with a landscaping rake.

Ensure Seed-to-Soil Contact

Small-seeded annual and perennial seeds, especially wildflowers, require seed-to-soil contact to successfully germinate and establish. Compaction of the seedbed after sowing is extremely important for success. Culti-packers and lawn rollers are both very effective tools for pressing the seeds into the soil.

Maintain: Irrigate the 1st Year & Mow Once Per Year in Late Fall

Once established, these mixes require very little care. During the first year, however, irrigating the stand with ¼ to 1 inch of water per week can help establish slow-growing perennials. We recommend mowing your insectary mix once each year in the late fall, after the last flowers have finished blooming.

Small but Mighty

Beneficial insects go about their business in countless, complex ways that are integral not just to agriculture but to the entire web of life. Of all the crop plants commonly grown around the world, a large majority are more or less dependent upon insects—both for pollination, competitive pressure against pests, and a wide variety of other ecosystem services. Without them, our lives would be very different, our diets very poor and strange indeed. A resourceful grower is one who provides them safe haven and puts their small but mighty talents to good purpose.