- Carrot Growing Guide | Fundamentals of Bed Preparation, Spacing, Weeding & Watering - Part 1

- Collinear Hoes | Tech Sheet (PDF)

- Connecta® Tool System | Assembly & Maintenance | Tech Sheet (PDF)

- Finger Weeders | Instruction Manual (PDF)

- Flame Weeder | Assembly, Backpack Tank Mounting, Usage & Safety Instructions | Tech Sheet (PDF)

- Glaser Wheel Hoe | Double Wheel Conversion Kit | Instruction Manual (PDF)

- Glaser Wheel Hoe | Instruction Manual (PDF)

- Offset Wire Hoe Assembly Instructions | Tech Sheet (PDF)

- Tine-Weeding Rakes | Instruction Sheet (PDF)

- Video: Tine-Weeding Rake Demonstration

- Video: Jack Algiere Demonstrates the Tine-Weeding Rake

- Video: Wire Weeder | Improve Weed Control on the Small Farm

- Video: How to Use & Handle a Silage Tarp to Create a Stale Seed Bed

- Video: Eliot Coleman Demonstrates How to Use Johnny's Collinear Hoe

- Video: Johnny's Flame-Weeder Demonstration

- Video: Using the Glaser Wheel Hoe | Demonstration by Johnny's Selected Seeds

- Video: Johnny's Long-Handled Tools

- Weed Barrier Fabric | Instruction Sheet

- Got Weeds? Targeting Annual & Perennial Weeds

- Weed Management for Sustainable Agriculture | A Two-Pronged Approach

- Long-Handled Weeding & Cultivation Tools | Old & New Favorites

- Wheel Hoe Selection Guide | Tech Sheet (PDF)

- Wheel Hoe Selection Guide - Find Your Fit

- Johnny's Flame Weeder – 30"

- Connecta® Bed Prep Rake | Connecta Tool System

- Johnny's Flame Weeder Backpack | Instructions for Use | Tech Sheet (PDF)

- Johnny's Flame Weeder – 30" | Assembly & Use | Tech Sheet (PDF)

- Terrateck Wheel Hoe Assembly & Instruction Manual | Single and Double Wheel Hoe | in English | (PDF)

- Connecta® Stirrup Hoe | Connecta Tool System

- Table of Wheel Hoe Attachments & Compatibilities | Glaser & Terrateck Options from Johnny's

- Video: Connecta® Interchangeable Tool System from Johnny's Selected Seeds

- Cover Cropping for Field & Garden | Johnny's Educational Webinar Resources

Weed Management in Sustainable Agriculture

A Two-Pronged Approach to Season-Long Weed Control

In sustainable agriculture systems, a comprehensive weed management strategy involves a deliberate, two-pronged approach:

- Reduce the existing weed seedling density and the weed seedbank.

- Block additional weed seeds from gaining a toehold.

Effecting the first of these can be much more time- and labor-intensive than the second, but when they are implemented in tandem, the two phases work together to maximal effect.

Here are the basics of this dual approach.

MAKE SEVERAL PASSES — WITH THE RIGHT TOOLS

To reduce the density of weeds competing with their crops, many farmers and gardeners focus solely on "weeding," meaning cultivation or hoeing.

The working rate for a weeding technique is the time required to effectively complete the task. Working rates follow a predictable order:

Photos courtesy Eric Gallandt, University of Maine

- tractor cultivation;

- push tools (for example, wheel hoes);

- long-handled tools;

- short-handled tools; and

- lastly, the slowest method, hand pulling.

For tractor cultivation or wheel hoes, working rates are the same over a wide range of weed densities, but some weeds will inevitably escape these events. Hand pulling and/or hoeing, on the other hand, can provide 100% weed control, but with time and cost increasing in proportion to the density of weeds present.

The takeaway? Making several passes with tractor-mounted or push-tools can contribute to an efficient weeding strategy.

For more information, see Evaluation of Scale-appropriate Weed Control Tools for the Small Farm, a Northeast Sustainable Agriculture Research & Education (SARE) project.

Associate Professor of Weed Ecology & Management

University of Maine, Orono

Dr. Gallandt's research program is focused on ecologically-based weed management in organic farming systems, with recent projects examining hand tools for small-scale producers, sources of variability in cultivation, weed seed predation, and strategies to manage weed seedbanks.

Dr. Gallandt is also an instructor in UMaine's Sustainable Agriculture undergraduate program, the first such BS program in the US, established in 1988.

TARGET SMALL WEEDS

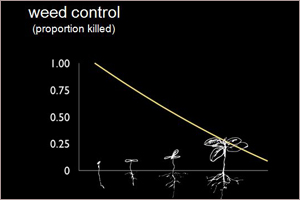

Cultivators, including hand tools, kill only a proportion of the weed seedlings present. Generally, this "weeding efficacy" is greatest for very small weed seedlings, especially in the "white thread" stage, and declines considerably as weeds get larger.

Some large-seeded weeds have considerable root biomass even at the cotyledon stage of growth, and are more difficult to control with cultivation than small-seeded weeds. An example is shown in the photo of hempnettle and wild mustard (large-seeded) vs. the white-thread common lambsquarters and redroot pigweed seedlings (small-seeded).

MORE WEEDLINGS = MORE CULTIVATIONS

Invariably, some weedlings will survive. It is important to note that the density of surviving weeds, or "escapees," is proportional to the initial density. In other words, more weed seedlings equals more survivors.

Thus, as weed pressure increases, the number of cultivation events will have to increase to keep pace.

Reversing this trend of increasing weeds and weeding cost requires a more comprehensive weed management plan, one that includes late-season efforts to:

- prevent annual weeds from going to seed; and

- prevent perennial weeds from building up below-ground energy reserves.

WEED WHEN IT'S DRY

Physical weed control generally relies on slicing, uprooting, or burying small seedlings.

In moist soil conditions, seedlings are more likely to re-root and continue growing. For example, in a field corn cultivation experiment, we found our weed control efforts decreased in proportion by 8% with each 1% increase in volumetric soil water.

The takeaway? Cultivation is more effective in dry soil conditions.

PLANT INTO A STALE SEEDBED

Annual weeds respond to a wide range of environmental cues that stimulate germination, including light, water, oxygen, nitrogen, and so forth.

If beds are prepared in advance, they should be shallowly worked (to a depth of 2", or approximately 5 cm) immediately before planting, to kill emerging and established seedlings.

Flame-weeding is another option for creating a stale seedbed, a technique that is particularly useful in slow-to-emerge crops such as carrot or beet. Flaming should target annual broadleaf weeds; grasses, with their basal growing points, are less susceptible. Ideally, flaming should be performed a day or so before crop emergence; if the ground is cracking and the crop is starting to emerge it can be killed by the flame. Flaming can also be used in the fall as part of a seedbank management program.

To learn more, watch the UMaine Weed Ecology Group's Seed Flaming Project video…

2 • PREVENT WEED ESTABLISHMENT

MULCH CROPS TO SPREAD WEEDING WORKLOAD

Plastic and organic mulches can serve several purposes. They can:

Student CSA team applies 1"-thick mulch hay between beds, overlapping red plastic mulch.

Photo courtesy Eric Gallandt, University of Maine

- modify soil temperature;

- conserve moisture; and

- provide season-long weed control, thereby freeing labor to focus on weeding crops that require cultivation.

Plastic mulches are widely used for heat-loving vegetables (eg, tomatoes, peppers, eggplants, melons, basil), but can also be applied on a wide range of other crops (ie, crucifers, other cucurbits, onions, garlic, head lettuces, cut flowers).

Managing weeds in the wheel tracks or paths between plastic-mulched beds remains a challenge, however. In our small-scale student CSA, we use a heavy application of mulch hay between the beds, aiming for a depth of at least 1" (~2.5 cm) of compressed mulch, to provide season-long weed control. The mulch must maintain this thickness, overlapping the plastic, to avoid weed problems on this edge. While costly, both for the mulch and the labor, we are pleased with this system as it both benefits soil quality and spreads the students' weeding workload; nearly half the enterprise does not need subsequent weeding.

Living mulches are another option for the areas between plastic mulched beds, but compared to straw, hay, or leaves, the living mulch will compete with the crop for water and nutrients, and provide an environment more favorable for perennial weeds to proliferate. If living mulches are used, consider strategies to manage the competition. For example, drip irrigation and band application of fertilizers can be used to deliver water and nutrients to the crop; frequent mowing can manage resource uptake by the living mulch.