- Cantaloupe Melon Varieties | Comparison Chart (PDF)

- Video: 'Lambkin' Piel de Sapo Melon | How & When to Harvest

- Farm Visit: Mark's Melon Patch – Dawson, Georgia | Johnny's Selected Seeds 40th Anniversary

- Video: How to Tell When Your Charentais-type Melons Are Ready for Harvest

- Melons (Cucumis melo) | Growing Instructions / Technical Production Guide (PDF)

- Melons | Key Growing Information

- Melon Growing Basics | Seed Starting, Transplanting, Culture, Harvest Indicators, Storage & Shelf Life

- Video: Harvesting Your 'Lilly' Crenshaw Melon

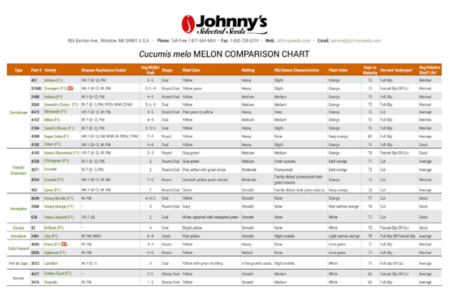

- Melon Varieties (Cucumis melo) | Comparison Chart (PDF)

- Cucumber Beetle Lure Instructions | Tech Sheet (PDF)

- Video: Galia Tropical Melon Harvesting | When to Slip off the Vine

Types of Melons & the Basics of Successful Melon Growing

By Nathaniel Gorlin-Crenshaw, Product Manager, Johnny's Selected Seeds

A perfectly ripe, locally grown melon is one of the greatest treats of the produce world. Sweet and fragrant, with a texture that practically melts in the mouth, a fresh, well-grown local melon bears little resemblance to its supermarket counterpart. Most of the melon varieties commonly found in the supermarket have been bred to withstand the rigors of shipping and handling: these varieties have harder flesh to resist bumps and bruises through the packing line and in transit, less sweetness and reduced aromatics in favor of an extended shelf life, and are often picked before they are fully ripe. For most of these varieties, the eating quality that the consumer experiences after buying the melon is secondary to traits that support shipping and handling.

The Johnny's melon assortment has been specially selected to only include varieties that have passed our rigorous standards of sweetness, texture, and flavor, while still ensuring the same strong agronomic qualities and adaptability to challenging growing conditions we know our customers need. Our melons provide a unique opportunity for both the passionate home gardener and for growers selling locally, who will be able to eat or sell a product generally not available in supermarkets. And once consumers taste such a melon, they will not go back to the supermarket types: with the right varieties and knowledge, you can produce melons that will win over the pickiest eaters and the most discerning buyers, chefs, and friends.

This article is about growing melon types and cultivars in the species Cucumis melo, which includes a diverse range of both netted and smooth melons, but not watermelons. As a group, these are the melons sometimes referred to as hard-shell melons or winter melons.

Watermelons are a different genus and species, Citrullus lanatus var. lanatus, although both types are members of the Cucurbitaceae (cucumber family).

Melon Types

At their broadest definition, melons are members of the cucurbit family (Cucurbitaceae) but are a botanically diverse group of crops, that fall across several different genera. For our purposes however, this article will focus on what are typically referred to as “true” melons: those varieties belonging to the species Cucumis melo. Even here, though, there are subgroups, some of which can be a bit nebulous even to the experienced melon grower: we’ve created two general categories to help provide some structure and context to what might otherwise feel like an overwhelming assortment:

Netted Melons

Assortment of cantalope (muskmelon) varieties. These types have the iconic, aromatic, "musky" aroma and sweet taste.

This category broadly refers to two sub-groups of Cucumis melo: C. melo var. cantalupensis, and C. melo var. reticulatus. Both sub-groups typically have netted rinds when fully ripe (though some melons within cantalupensis are more lightly checked/netted), highly aromatic flesh, and can be managed in much the same way in terms of growing, harvest, and storage.

Cantaloupe

“Cantaloupe” and “muskmelon”, while often referred to interchangeably, are actually a fairly wide category of melons, including members of both C. melo var. cantalupensis and C. melo var. reticulatus, respectively. Regardless of formal classification, these types have the iconic, aromatic, "musky" aroma and sweet taste. Two sub-categories of cantaloupe that Johnny’s carries are:

- Eastern: As the name implies, these types were traditionally grown more predominantly on the eastern side of the US. They are distinguished by their deep ribbing (also called sutures), less spherical shape, and their fully straw-colored rind which has less consistent netting. Their flesh is orange in color, and their seed cavities tend to be a bit larger—as a type they were often bred for more direct markets and immediate consumption, rather than long-shelf-life and long-distance shipping.

- Tuscan: Originating in Italy, these types have elements common to the eastern cantaloupe: they tend to have a smaller seed cavity and more pronounced netting, but a less-spherical shape and deep ribbing similar to eastern types. More notably, the ribs are grey-green on immature fruit, eventually lightening to light green or yellow as the fruit matures, in contrast to eastern types, where the ribbing is the same color as the rest of the fruit.

Charentais (French)

Originating in the mild, fertile Charentes region of West-Central France, the Charentais are some of the most revered melons in the world. Uncommon at big-box stores because their thin skin and soft flesh make them difficult to ship without damage, these small French melons fall into the cantalupensis group, with flesh similar to cantaloupes but even more highly aromatic: they often have a more floral flavor and fragrance, with notes of jasmine and honeysuckle. The rind, which may range from only slightly checked to fully netted, will have characteristic ribs running from stem to blossom-end. Readiness can be trickier to determine than most other netted types. (See section on Ripeness Indicators.)

Galia (Tropical)

These round-to-slightly-oval melons are a fairly recent development, with the first variety being released in 1973. They were originally created by an Israeli melon breeder who named them “Galia” after his daughter. Their thick, lime-green flesh is smooth, sweet, and complex in flavor, suggestive of tropical fruit with a fresh, banana-like aroma. In the reticulatus group alongside muskmelons, the rind of Galia melons has a dense corky net like a cantaloupe, but without ribbing.

Smooth-Skinned Melons (the “inodorous” group)

Honeydew, piel de sapo, canary, and crenshaw melons, among others, are all generally classified as Cucumis melo var. inodorous, which as a group tend to have smooth skin and a milder flavor/aroma compared to the netted types. These types are also sometimes referred to as “winter” melons, (though this is not to be confused with Benincasa hispida, which shares this same common name) as many of these types are late to mature and store well into the winter months given the right conditions. “Oriental” or Asian melons can also be generally grouped into this category, though they belong to Cucumis melo var. makuwa.

Canary

Canary melons have a subtle flavor often reminiscent of more tropical fruit.Traditionally grown in Spain and in parts of Asia, canary melons are oval-to-oblong melons which get their name from their distinctive bright-yellow skin, which becomes waxy when the fruit are fully ripe. The juicy, cream-colored flesh is very sweet and slightly coarse, like a soft pear, and has a subtle flavor often reminiscent of more tropical fruit.

Crenshaw

Crenshaw melons are large and oblong, with a pale-yellow rind and containing a creamy, sweet orange flesh. Their superb flavor is among our favorites at the Research Farm, and not just because our Melon Product Manager shares his last name with this type! Crenshaw melons are often described as tasting like a cross between a honeydew and a cantaloupe, with floral notes and a subtle spiciness.

Honeydew

Honeydew melons are often characterized by their firm flesh, smooth rind, and lack of a musky odor.Honeydew melons are often characterized by their firm flesh, smooth rind, and lack of a musky odor. Familiar to many people due to their prevalence in store-bought fruit salad, Johnny's honeydew cultivars offer earlier maturity, sweeter taste, attractive appearance, and a smaller (medium) size than typical grocery store honeydews. Additionally, while Honeydew melons typically grow best in semiarid climates, our varieties have been selected at our Maine Research Farm; they develop a high sugar content even under cool and cloudy conditions, and are tolerant of conditions that normally cause cracking.

Oriental/Asian

Crisp and refreshing, Asian types are often favored by people who find other melons to be too sweet or musky.Grown in many countries around central and eastern Asia, oriental melon types tend to be oblong in shape, with a golden-yellow rind and crunchy white flesh. Crisp and refreshing, these types are often favored by people who find other melons to be too sweet or musky. Johnny’s has specifically selected strains that mature very early and that can handle cooler weather conditions compared to other types of melons.

Piel de sapo

Piel de sapo melons have a sweet, mild flavor similar to honeydew and canary melons.Originating in Spain, piel de sapo means "toad skin," a testament to the distinctively thick, blotchy-green and yellow-speckled rind of this type. Despite the unappetizing name, piel de sapo melons are a popular type outside of the US, and have a sweet, mild flavor similar to honeydew and canary melons. Piel de sapo have pale-green-to-white-colored flesh, with a crisp, juicy texture, and good sweetness. Piel de sapo as a type tend to be very late to mature, leading them to also be known as Christmas or Santa Claus melons, as typical older varieties still tend to be very large and extremely late-maturing. 'Lambkin' is smaller and much earlier to mature than any other piel de sapo variety we’ve found.

Succession-Planting Melons

Multiple succession plantings is the recommended way to stagger ripening of your melon crop and extend the harvest window. Although there is some opportunity for making a single planting of varieties with staggered days-to-maturity, it is limited. While you could do one planting of especially early and especially late maturing varieties, in general, most melons have relatively similar days-to-maturity, making multiple plantings more effective for extending the harvest. Periods of especially hot and stressful weather can also cause varieties with different days-to-maturity to “bunch together” in terms of their ripening, making multiple plantings especially helpful to avoid this. Plants can be set out after the danger of frost has passed, though care should be taken not to plant too late into the summer: later plantings risk having too short a remaining growing season left for fruit to fully mature. See our Comparison Chart of Melon Varieties to review distinguishing characteristics and features, including days to maturity.

Getting Your Seedlings off to a Strong Start

Melons are heat-lovers and tender by nature, and although they can be direct-sown outdoors, we recommend this only under the warmest, most favorable growing conditions. Most growers find that starting seed indoors tips the odds in their favor by:

- Improving germination rates

- Preventing damage by hungry cutworms

- Discouraging damping-off of seedlings

- Getting a headstart on planting in shorter growing seasons

For indoor seed-starting, time your first sowing date to about a month before transplanting, so the seedlings don't get oversized. Tall, thin, “leggy” seedlings are especially prone to physical damage and transplant shock.

Sow 2–3 seeds, ¼-inch deep in cell flats. To further prevent damping off, use a slightly drier medium than typical for most other crops. Water with care and allow medium to become moderately dry between waterings. Adequate air circulation is essential. If necessary, position small fans over greenhouse benches.

To avoid root damage when transplanting, grow melons in large cells so the plants can size up sufficiently before setting out. We use 50 cell plug flats on the Johnny's Research Farm.

Place the trays on a heat mat, set at 80–90°F (27–32°C) until the seeds germinate. After germination, dial the mat temperature back down to 75°F (24°C) to grow the seedlings.

When the plants have developed a couple sets of true leaves, they've reached the transplanting stage. They will need to be hardened off for about a week, however, by reducing temperature and water, before moving them outdoors.

Transplanting

When there is no longer any danger of frost and the weather is warm and settled, you can transplant the seedlings, spacing them 18 inches apart, in rows 6 feet apart. Melon seedlings are still tender even when hardened off and handling them gently will minimize transplant shock and enhance field performance.

Immediately after transplanting, water them in with a fertilizer solution. We use an organic fish emulsion, as it delivers a good nutrient boost without burning the tender transplants.

Melons are typically grown on plastic mulch to warm the soil and prevent weeds. In cooler areas, solar mulch is recommended because it warms the soil better than black plastic. In the South, most growers grow melons only in spring to avoid the high heat of midsummer, though some also grow a fall-maturing crop.

Watering/Irrigation

Melon plants are thirsty and should be irrigated regularly—but only up until the fruits grow to full-size—not full ripeness. Drip irrigation is recommended to prevent excess water on foliage, which can lead to disease. During the fruit ripening stage, the qualities of texture and flavor develop, and the crop should not be watered unless the plants are showing obvious signs of heat stress, such as wilting. Irrigating while the fruits are ripening can result in bland, watery fruits.

Pests & Diseases

The primary pest problem for melons in the Northeast is the cucumber beetle, which can kill seedlings, severely damage the foliage and developing fruits, and can also spread bacterial wilt (Erwinia tracheiphila). To protect from cucumber beetles, most growers cover newly transplanted crops with row cover immediately after transplanting. We recommend AG-19 as it provides added warmth as well as insect exclusion. Hoops are not needed, though they can be helpful in windier areas: on occasion, high winds may cause row cover to abrade the plants, but usually the damage is minimal and they will grow out of it.

Many growers will also protect young seedlings with Kaolin clay (Surround), which forms an effective film barrier, protecting plants from pests by repelling them, causing irritation and confusion, and preventing feeding and egg-laying. Kaolin clay also protects against sun damage and reduces heat stress, cooling plants by 10–15° F. Typical application is by sprayer, but whole trays of seedlings can be dipped for early protection.

Finally, placing low tunnels with vented plastic over the rows is another option, if melon prices justify the added expense. Low tunnels also protect the crop from excessive rain and provide more heat for young plants, allowing for earlier spring crops and later fall crops.

Pollination

To set fruit, melon plants must be pollinated. Once the vines begin to run and the first flowers appear, be sure to remove the covers or tunnels, or roll up the sides during the day, to allow access to pollinating insects. You may also find setting hives worthwhile, to aid pollination and improve yield.

Melon Ripeness Indicators & Harvesting

Knowing just when to harvest a melon crop is part art and part science, but a skill you can acquire through observation and practice. To start, there are signs that herald the approach of peak ripeness or indicate its presence for the various types. How much time you expect to pass before the melon will be eaten is the other major consideration (more about this below).

Telltale signs to watch for. Visible or palpable changes at ripeness can involve the following:

- Rind

- Change in skin cast or coloration.

- Cracking, striations, or other markings.

- Slight softening of the fruit.

- Juncture of fruit stem and vine

- Browning and shriveling of tendril and/or leaf most proximal to fruit stem.

- Shrinking of the area where stem attaches to the fruit. When this occurs, it's time to test for ripeness. This is the primary clue growers use to assess ripeness, as it is characteristic of the melon type and relates to how the fruit is usually removed from the vine.

Removal from the vine. At ripeness, some melons "slip" from the vine easily or with a bit of a tug, whereas others must be cut. there are three general categories:

- Full-Slip: Ripe fruit can be easily detached from the stem with a slight tug or a gentle push of the thumb against the peduncle.

- Forced-Slip: Also known as Half-Slip. Ripe fruit requires an extra-firm push of the thumb against the stem to detach it from the fruit—more pressure is needed than with full-slip types, but the fruit can still be harvested without cutting the stems.

- Non-Slip: Also called cut-from-the-vine types. Ripe fruits need to be cut at peak ripeness from the vine at harvest. These types would be very overripe if left until they slipped from the vine, if they ever slipped at all.

When the intention is to ship or store a melon crop, some growers elect to time the harvest to occur before peak ripeness—harvesting full-slip types early at the forced-slip stage, or harvesting forced-slip types early by cutting them from the vine. Take note that these practices will compromise the flavor.

The timing of when to harvest a melon is specific to the variety. However, different types of melons tend to fall together into one of these three categories. We’ve described some general category rules below—but remember, there are always exceptions on a variety level. Please check our Melon Comparison Chart for more specific details.

- Cantaloupe: in general, this type is ripe when the rind color transitions from a greenish cast to a warmer, straw-color and fruit slips easily from the vine. Tuscan types have the added ripeness indicator of the green ribbing changing from a gray-green to a light green or yellow color. Some varieties bred for longer shelf life are forced-slip or even no-slip, but the majority are still full-slip.

- Galia/tropical melons: these are ready to harvest when the fruit rind has turned yellow and develops small cracks where it encircles the stem, indicating the fruit can be slipped from the vine with a gentle tug (full-slip).

- Piel de sapo: as fruit approaches ripeness, the background color of the rind turns from green to yellow, though the fruit will maintain some green spots, reminiscent of its namesake. There are two common harvest methods for this type, depending on your needs and preferences. Melons can be harvested early by cutting from the vine to prolong shelf life; or, for best flavor, allowed to remain on the vine to develop full potential, then harvested at full slip.

- Canary: harvest at forced slip, when the fruit turns rich, canary yellow and the blossom end of the fruit yields slightly to a gentle press of the thumb. (Fruit can also be cut from the vine slightly earlier to prolong shelf life.)

- Crenshaw: ready to harvest when the skin is a creamy yellow and the fruit is slightly soft to the touch. They typically can be harvested at either full or forced slip: fruit left on the vine a couple of extra days will be a bit riper and tastier, though they won’t store as well.

- Oriental: harvest when fruits turn slightly golden, at forced slip, or cut from vine. Even at full ripeness these types are less sugary than other melons, with a mild flavor reminiscent of cross between a honeydew and a cucumber.

- Charentais: ready to be cut from the vine when the smallish, long-stemmed leaf next to the fruit becomes pale, and the small tendril nearest to where the fruit attaches to the vine turns brown. Another indicator is a yellowish "warming" of the skin (whereas orange skin color indicates the fruits are overripe).

- Honeydew: like Charentais, honeydew have a small, long-stemmed leaf attached to the vine, opposite to where the fruit is attached, which turns yellow when the melons are ripe. Ripeness is also indicated by a "warming" of the skin tone. Harvest by cutting from the vine.

For more details on when to harvest the various types of melons, refer to the variety descriptions given on our product pages. With practice you will learn to harvest your melons at peak ripeness.

Melon Storage & Shelf Life

The storage conditions and periods listed here are approximations—the variety of melon and the ripeness of the fruit at the time it is harvested, among other factors, will affect its shelf life. Here are some guidelines.

Storage Conditions

- Netted melons store best at 36–41°F (2–5°C) and 90–95% humidity. Chilling injury can occur at temperatures below 35°F. These types produce ethylene and are sensitive to it.

- Smooth-skinned melons should be stored at 45–50°F (7–10°C) and 85–95% relative humidity. Chilling injury can occur at temperatures below 45°F. These types tend not to produce ethylene and are much less sensitive to it compared to netted melons.

- All melons will hold for a few days without refrigeration, but will hold longer if chilled. With regard to eating quality, there can be a flavor penalty with chilling melons. Chilling can dull flavor, especially over time, and melons are generally juicier and softer if kept at room temperature for 1–2 days before serving. Nevertheless, many people prefer to eat their melon chilled, particularly in hot weather.

Storage Potential

Melon shelf life can be ranked as follows:

- Minimal Shelf Life: cantaloupe and galia will hold for 2–3 days at room temperature, 7–10 days if refrigerated. The cantaloupe variety 'Athena' stores better than average, but with storage its flavor may not equal that of our other cantaloupes.

- Average Shelf Life: charentais, crenshaw, and piel de sapo types will hold for 4–5 days at room temperature, 7–12 days if refrigerated.

- Good Shelf Life: canary and honeydew will hold for 7 days at room temperature, 10–14 days if refrigerated.

Learn More

Growing your own melons is a worthwhile endeavor. There is a learning curve but once you've mastered the fundamentals, melons can be a rewarding and profitable crop. Best of all, you can choose the types and cultivars to grow: no more bland melons for you, your family, friends, or customers. With the right varieties and know-how—even if your summers are short and cool—you can produce melons with premium appearance, quality, and flavor.

If you're thinking of including melons in your growing plans this year, give us a call and let us help. Below are some additional resources to get you started.

Johnny's Resources

- Cucumis melo Melon Varieties • Comparison Chart (PDF)

- Cantaloupe Varieties • Comparison Chart (PDF)

- Cucumis melo Melon Harvesting Tutorials • Videos

- Cucumis melo Melon Production • Tech Sheet (PDF)