- Webinar Slide Deck | Soil Health and Management Strategies | PDF

- Exceed Garden Combination Inoculant | Information Sheet (PDF)

- Exceed Pea, Vetch & Lentil Inoculant | Information Sheet (PDF)

- Alfalfa & True Clover Inoculant | Label

- The Amazing World Beneath Our Feet: An Introduction to Soil Health

- Exceed Peanut Cowpea Lespedeza Mung Bean Inoculant | OMRI Certificate

- Soybean Inoculant | Label

- Exceed Alfalfa/True Clover Inoculant | OMRI Certificate

- Organilock | OMRI Certificate

- Cover Cropping for Field & Garden | Johnny's Educational Webinar Resources

- Exceed Peat Rhizobium Inoculants | SDS (PDF)

- Exceed Garden Combination Inoculant | OMRI Certificate

- How to Make Compost for Your Garden • Tutorial with Niki Jabbour

- Farm Seed Information Library | Johnny's Selected Seeds

- Implementing No-Till Farming Practices

- Exceed Pea, Vetch & Lentil Inoculant | OMRI Certificate

- Trap Wire Compost Bin & Add-on Bin Assembly | Tech Sheet (PDF)

- How to Make Compost in 4 Easy Steps | Tech Sheet (PDF)

- Soil Health and Management Strategies | Johnny's Webinar Series

- Video: Soil Health and Management Strategies | Webinar Recording

- Exceed Soybean Inoculant | Information Sheet (PDF)

- Exceed Alfalfa/True Clover Inoculant | Information Sheet (PDF)

- Inoculants | General Information Sheet

- Exceed Soybean Inoculant | OMRI Certificate

- Exceed Peanut Cowpea Lespedeza Mung Bean Inoculant | Label

- OK to Compost Certificate | 22mm Compostable Trellis Clips

Intro to Soil Health: The Amazing World Beneath Our Feet

By Collin Thompson, Farm Operations Manager, and Jill Porchetta, Farm Technician III, Johnny's Selected Seeds

Good soil is the basis of successful food production, the nutrient density of our crops, and in turn, our health. The ideal soil for growing most vegetables, flowers, and fruit is deep, friable, and well-drained, with adequate available nutrients to support optimum plant growth. A few lucky growers have those conditions on their land, but most of us have less-than-perfect soil that requires some work to get it into shape and keep it healthy. The work will pay off in the future with crops that have higher yields, fewer pest and disease problems, and stronger resilience in the face of extreme weather.

What is Soil Health?

Prepping beds at the Johnny's Research Farm where we alternate rows of cash crop with rows of cover crop.

Soil health is the ongoing capacity of soil to function as a living ecosystem that sustains life. Key components of soil health include:

- Physical structure (texture and structure, a.k.a. tilth)

- Chemical composition (pH and nutrient levels)

- Biological life (microorganisms, small invertebrates, and fungi)

Healthy soil serves multiple critical roles in the farm and garden; it:

- Supports plant growth and enhances the nutrient density of crops;

- Reduces erosion, enhances water retention, and promotes adequate drainage;

- Builds resilience against pests and diseases;

- Sequesters carbon, reducing the climate impacts of agriculture.

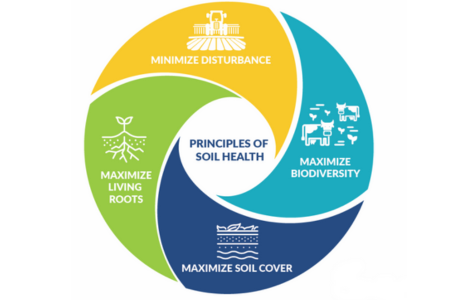

4 Soil Health Fundamentals

When we think about how to nurture soil health, there are four basic principles to keep in mind. These soil health fundamentals apply to all soils and scales of farming and gardening. Adhering to these principles helps us to achieve optimum soil health by mimicking nature.

- Minimize soil disturbance (for example from tillage, synthetic fertilizers, and pesticides)—minimizing disturbance helps maintain soil structure, promote healthy populations of soil micro-organisms, and helps reduce the evaporation associated with tillage.

- Maximize living roots—it is ideal to retain living roots in the soil for as much of the year as possible; plant roots house and nurture soil life and protect soil from erosion and temperature extremes.

- Maximize soil cover—when we can’t rely on living roots, mulch, straw, or terminated cover crops can help protect the soil.

- Maximize biodiversity—a diversity of cover crops and cash crops creates a more diverse community of soil microbes. Additionally, supporting aboveground biodiversity can enhance nutrient cycling and pollination services.

Physical Properties of Soil (Tilth)

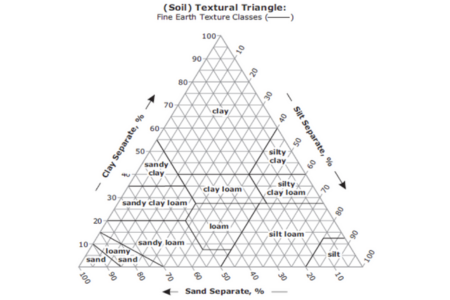

Tilth refers to the physical condition of the soil, and how well it allows for essential plant processes including seed germination, root growth, water infiltration and drainage, and root aeration. A soil’s native texture is directly related to the size of soil particles. Soil is made up of three different particle types: silt, clay, and sand. Sand is the largest soil particle. Silt particles are much smaller, and clay particles are smaller yet.

It is helpful to understand the makeup of your own soil because soil composition affects how the soil responds to your management strategies. For example, because of the large particle size, sandy soil drains water and nutrients relatively quickly whereas clay soils will hold on to water and nutrients for longer.

Most soils will be a mixture of the three particle types in different percentages. For example, loam is an equal mixture of sand, silt, and clay. Soils that trend towards more clay, silt, or sand, are identified accordingly, for example: sandy loam, silt loam, or clay loam.

Home “Jar Test” for Determining the Physical Composition of Your Soil

Follow these steps to test your soil composition at home.

- Collect a soil sample and sift out bark, twigs, or stones. You will want to take soil from several parts of your field or garden and mix the samples together to achieve an average.

- Fill jar 1/3 full of soil.

- Fill remainder of jar with water.

- Put a lid on it and shake it well until everything is in suspension.

- Set on a level surface for 1 minute, measure and mark the sand layer (sand settles first because it’s heaviest).

- Return after two hours, measure and mark silt layer.

- Return after 48 hours, measure and mark clay layer.

- Measure the height of each of the layers. Determine the percentage of each.

Chemical Properties of Soil

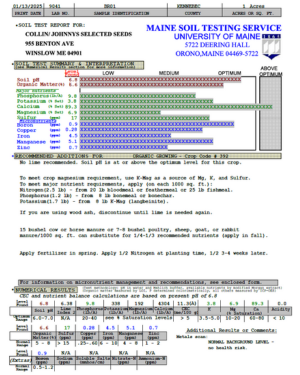

Example soil test results.

Our goal in understanding the chemical properties of our soil is to kickstart the biological flywheel; to ensure that the soil microbes are thriving and that the soil is able to cycle nutrients and make them available to our garden crops.

First Test, Then Amend

We highly recommend getting a soil test from your local extension office. For about $20, you will receive a wealth of information about your soil. You’ll get data on the pH, macronutrients, micronutrients, organic matter %, cation exchange capacity (the soil’s ability to retain nutrients), and basic amendment recommendations based upon what you have indicated you are planning to grow. Generally speaking, the primary areas to focus when adjusting your soil are pH, soil organic matter, and nutrient deficiencies.

How to Take a Soil Sample to Test

- Use a soil probe to take core samples from around your garden/field. If you do not have a soil probe, use a shovel to dig a hole 6-8”, then take a thin vertical slice from the side of the hole to get a sample that includes soil from the entire 6-8” profile.

- Mix the soil together (this helps you get a good average for the entire plot) and package approximately a cup of soil in a soil test box or plastic bag.

- Mail it to your testing lab, following the lab’s packaging and labeling requirements.

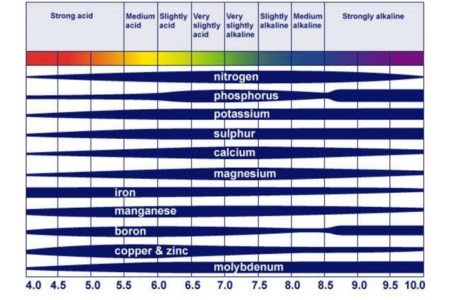

Soil pH (Soil Acidity)

Soil pH has a profound effect on both soil biology and the efficacy of fertility amendments. pH is a measure of soil acidity: 7 is neutral, below 7 is acidic, and above 7 is alkaline. The availability of plant nutrients varies significantly at different soil acidities. Between 6.5 and 7 is where most garden crops thrive; it’s where most critical nutrients are close to their maximum availability. If you target 6.5–7 you will capture most of the macro and micronutrients for most garden crops. There are exceptions of course (like blueberries, which love acidic soil). Most soil microbes also like that sweet spot where they will be most effective at digesting, mineralizing, and recycling organic matter, helping plants take up soil nutrients.

If your pH is off, start here! To raise the pH, apply agricultural lime or wood ash. To lower pH, use elemental sulfur, peat moss, or pine needles. Your soil test results will provide you with recommended application rates.

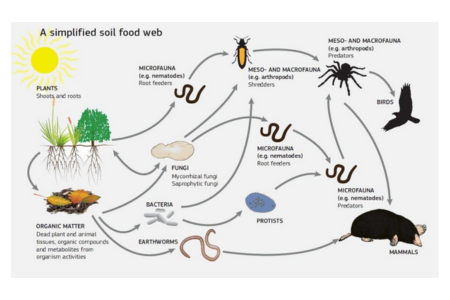

Biological Properties of Soil: The Soil Food Web

The soil food web consists of bacteria and fungi as well as protozoa, nematodes, insects, and small mammals. The soil food web stores carbon, makes nutrients accessible to plants and increases soil aeration and water infiltration. Biological activity in the soil is foundational to plant health and the plant immune system; we can think of the relationship between soil microbes and plants much in the same way as the microbiome in our gut is to our overall health, digestion, and immune system.

The soil food web begins in the rhizosphere, the immediate area around plant roots. Bacteria and fungi, the smallest organisms in the food web, consume carbon-rich exudates from the plant roots, break down organic matter in the soil, and immobilize (store) nutrients in their bodies. Protozoa and nematodes, the next largest members of the food web, consume the bacteria and fungi, mineralizing (releasing) these nutrients, making them available to plants.

There are several thousand species of bacteria and fungi in our soils. These species are foundational to facilitating upwards of 90% of nutrient uptake by plants. Here are just two examples that are particularly important to our garden plants. The symbiotic relationships between these microbes and plants have evolved over millions of years.

- Rhizobium bacteria partner with legumes (peas, beans, alfalfa, clover, vetch etc.) to convert atmospheric nitrogen into plant-available forms. These amazing bacteria live in the roots of the legumes where the plant feeds them carbohydrates and in exchange, the bacteria convert atmospheric nitrogen into a plant-available form. There are only a handful of ways that the triple-bonded nitrogen molecule can be broken, and this modest bacterium is one of them. Since our atmosphere is about 78% nitrogen, using legumes is a great way to put this free fertilizer into your soil.

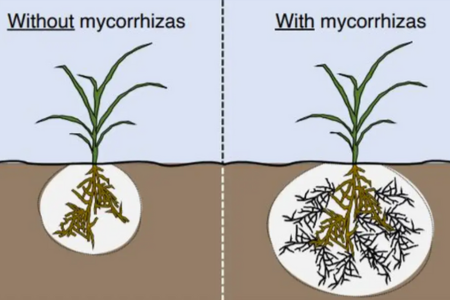

- Mycorrhizal fungi are another workhorse of the soil food web. They attach to plant roots and act as root extensions. They do this for around 90% of the plants on our planet. There can be miles of fungal hyphae (filaments, similar to roots) in just a teaspoon of soil. These hyphae can extend several feet away from the rhizosphere and transport otherwise inaccessible nutrients and water back to the plants. As an example, mycorrhizal fungi are capable of freeing and transporting phosphorus, which is often present in an inaccessible form in the soil. Because plants require large amounts of phosphorus to support growth, mycorrhizal fungi play a critical role in this exchange. In turn for the nutrients and water, plants feed the fungi carbon-rich root exudates. The fungi can’t live without the nourishment from the plant roots, so they protect the plants at all costs: they support and nourish them, enhance their immune systems, physically protect the roots from pathogens, and make the plants more resilient in times of stress.

Mycorrhizal fungi support many garden crops—such as beans, peas, sunflowers, carrots, onions, sweet potatoes, and many more. They do not partner with brassicas, buckwheat, spinach, beets, or—much to our advantage as gardeners—many of our common weeds such as lambsquarters, amaranth, pigweed, rush, and sedge.

Inoculants are formulated from peat-based cultures of beneficial bacteria for treating legume seeds prior to planting.

Feed Organic Matter to Your Soil Food Web

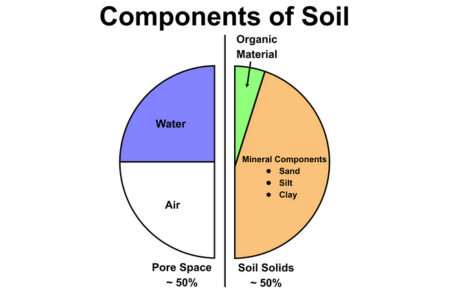

The major components of soil include: inorganic minerals, organic matter, water, and air.

Maricopa Community Colleges

Soil organic matter (SOM) comprises only a small portion of soil, from less than 1% to about 10% in the best of conditions, but it has an oversized importance to soil health. It contains almost all of the stable forms of nutrients that are slowly released in plant available forms as soil organisms decompose organic matter.

Soil organic matter is like your soil’s savings account. The microbial communities in your soil use organic matter as food, housing, and currency in their interactions with plants. Organic matter also contributes to good tilth, as it improves water-holding capacity, drainage, and soil structure. In fact, for every 1% of soil organic matter, your soil can hold roughly one inch of rainfall. High levels of organic matter help ensure a more resilient garden and healthier, higher-yielding crops.

Throughout the normal course of farming and gardening, we lose a lot of organic matter through:

- Tillage

- Harvesting

- Removal of crops/crop residue

- Application of synthetic fertilizers

To replenish organic matter in the soil, we need to put carbon-based amendments back into the soil. These can take various forms such as:

- Aged manure

- Compost

- Cover crop residue

Cover cropping adds organic matter to the soil in a few different ways. While the cover crop is living, the roots add organic matter through root exudates. After termination, the root mass breaks down to add more organic matter to the soil. After termination, the aboveground biomass also breaks down, adding organic matter to the soil over time.

You may also wish to add amendments to meet specific nutrient needs. Synthetic fertilizers are undesirable as they leach from the soil quickly, bypassing the processes of the soil food web. Natural amendments (such as gypsum, wood ash, blood meal, or kelp meal) are preferable. It is important to remember that our goal is to feed and nurture our soil food web, which will in turn feed our plants.

A visual indicator of soil health, rhizosheaths are a protective layer of soil adhered around roots, formed by root exudates and other biological glues sticking soil particles together.

Visual cues of soil health:

- Presence of visible soil life (indicates healthy microbial life)

- Rhizosheaths—A protective layer of soil adhered around roots, formed by root exudates and other biological glues sticking soil particle together.

- Dark color and crumbly texture.

Root Exudates

During photosynthesis, plants use energy from the sun, CO2 from the atmosphere, and water from the soil to make glucose. They use glucose as a building block to produce amino acids, proteins, starches, and cellulose—all that they need to grow—plus root exudates to feed the soil food web. In fact, up to 50% of a plant’s photosynthetic production goes to making root exudates.

Root exudates are carbon rich substances exuded from plant roots. They differ in composition depending upon the plant and the type of microbial community the plant is trying to attract. They can contain, for example, organic acids, carbohydrates, amino acids, and enzymes. With these root exudates, plants have a great influence on the soil around them.

The root exudates are used by the soil food web, and a large percentage become stored as humus (organic matter that exists below ground). While aboveground organic matter can be vulnerable to loss by oxidation, humus is more stable and can serve the soil for centuries.

Soil Armor—How to Keep the Soil Covered

The critical role of root exudates in building soil is a big reason why it’s so important to keep your soil covered with living roots for as long as possible throughout the year. There are several strategies to keep the soil covered; here we will detail two methods we use on our Research Farm.

Reduced Till System

At the Johnny's Research Farm, we use a reduced till system that alternates strips of cover crop and cash crop. Shown here is a field of cucumbers with a clover cover crop.

- We start with a fall planting of winter rye (an annual).

- In the spring, we drill or broadcast white clover as an underseeding. The clover will break through the rye residue in the spring and grow rapidly. It outcompetes the weeds, keeps the soil covered, fixes nitrogen into the soil, feeds the soil food web, and provides nectar for beneficial insects!

- We then prepare the beds—typically a single pass with a stone burier followed by another with a mulch layer.

- We plant our crops into the beds mulched in plastic. The footpaths between the rows remain in the clover cover crop.

- Periodically, we mow the clover to keep it manageable and to keep weeds from popping up.

- After about 3 years, grasses and weeds will creep into the clover, and we will need to start anew. At this point we will “flip the beds”—what was previously clover/footpath becomes garden bed and what was previously garden bed is planted in cover crop. The cycle begins again from step #1 above.

This reduced-till system, while not perfect, is a dramatic improvement over traditional tillage systems. It allows us to capture the benefits of plastic mulch (early soil warming, minimal soil splash, efficient irrigation, and weed suppression), while also contributing to soil health by having actively growing plants nearly covering the entire field.

No Till System

Here are the steps we use to achieve a fully no-till planting on our Research Farm:

A no-till plot of brassicas at the Johnny's Research Farm.

- Cover crop in early May with our Spring Green Manure Mix.

- After about 2 months, crimp the cover crop. The timing of cover crop termination is critical to ensure adequate amounts of mulch and fully terminated crop. For the Spring Green Manure Mix, we recommend following crimping with tarping for 1–4 weeks; tarp for longer if the temperatures are cool and shorter if the temperatures are warm.

- Transplant seedlings into the terminated cover crop.

Our no-till plantings have demonstrated reduced weed pressure and reduced need for irrigation. This system works best for transplanted crops like tomatoes, peppers, squash and brassicas.

Learn More

References Cited

- Mycorrhizal Fungi—Our Tiny Underground Allies, Adam Cobb

- Review of the Non-NPKS Nutrient Requirements of UK Cereals and Oilseed Rape, Roques et al., 2013

- Soil Biology, USDA Natural Resources Conservation Service (NRCS)

- Soil Health, USDA Natural Resources Conservation Service (NRCS)

- Soil Texture and Structure, USDA Natural Resources Conservation Service (NRCS)

- Soils, Maricopa Community Colleges

More Resources

- Benefits of Grass—Legume Combinations • Article

- Buckwheat: A Quick, Easy Summer Insectary & Weed-Control Cover Crop • Article

- Choosing a Spring Cover Crop • Article

- Cover Crop Decision-Making Tool • 5 Steps for Deciding What to Plant When & Where • Article

- Cover Crop Planting For Home Gardens & Raised Beds • Article

- Cover Cropping for Field & Garden • with Collin Thompson, Johnny's Farm Ops Manager • Webinar Resources

- Farm Seed & Cover Crops • Comparison Chart (PDF)

- Garden Cover Crops & Green Manures • with Collin Thompson, Johnny's Farm Ops Manager • Webinar Resources

- Implementing No-Till Farming Practices • Article

- Intro to Farmscaping: Insectary, Trap, & Repellent Crops for Pest Management • Article

- Soil Health and Management Strategies • Webinar

- Winter Cover Cropping: A Fine Time to Build Soil • Article