- 3 Easy, Reliable, Productive Cut Flowers: Sunflowers, Zinnias & Rudbeckia

- 5 Factors That Determine Vase Life of Cut Flowers

- 2019 American Flowers Week: Combining the Art of Floral Design & Couture

- Celebrate the 7th American Flowers Week | Johnny's 2021 Botanical Couture

- Celebrating the 8th American Flowers Week | Johnny's 2022 Botanical Couture

- Collective Selling Models for Flower Farmers: Flower Hubs That Work

- 5 Cool Flowers to Plant Now | Lisa Mason Ziegler's Secrets for Growing Hardy, Cool-Season Annuals

- Cut-Flower Harvesting & Post-Harvest Care | Best Practices from Pros in the Slow Flower Community

- Cut-Flower Kit | Guide for Market Growers (PDF)

- Easy Cut-Flower Garden Map | For Growers New to Flowers (PDF)

- Easy Cut-Flower Garden Planner | For Growers New to Flowers (PDF)

- From Color to Climate: 5 Floricultural Trends Subtle & Seismic

- Flower Culture by Crop | Comparison Chart | Days to Germination, Weeks to Transplant, Days to Harvest (PDF)

- Flower Farmers' Favorite Fillers & Foliage | Recommendations from 3 Farmer-Florists

- Getting Started in Cut-Flowers | Top 15 Cuts

- Heat & Drought: How Flower Farmers Are Adapting to Changing & Challenging Climatic Conditions

- Introduction to Overwintering Flowers | Guide to Overwintering Flowers

- An Introduction to Producer Marketing Cooperatives | M Lund & Associates

- How Day Length Affects Cut-Flower Production

- Growing Flowers in Hoophouses & High Tunnels: Cool-Weather & Hot-Weather Options

- Growing Flower Seedlings for Profit

- Roadside Flower Stand Basics: Success Tips for On-Farm Retail

- Starting a U-Pick Flower Farm, From A-to-Z

- Year-Round Flower Production Strategy

- Overwinter Flower Trials | Multiyear Results for 30+ Crops | Johnny's Selected Seeds | XLSX

- Seeding Date Calculator | Johnny's Recommended Flowers for Overwintering | XLSX

- Just Add Flowers | An Introduction to Companion Planting for Vegetable & Herb Gardeners

- Sustainable Farming Methods | A Survey of Flower Farmers' Best Practices

- Pricing & Profitability for Flower-Farmers | Pointers from a Diversity of Pros

- Slow Flowers Palette & Petal Crushes | Evolving Colors & Shape-Shifts in Floral Industry Trends

- Johnny's and Slow Flowers | Johnny's Selected Seeds

- Slow Flowers | Celebrating Fifth-Season Regional Design Elements

- Slow Flowers Floral Forecast | A Summary of Industry Insights & Trends

- Building a Better Market Bouquet: Tips, Techniques & Recipes for Flower Farmers

- Slow Flowers | Tips for Staging On-Farm Floral Workshops | Johnny's Selected Seeds

- Wedding Wisdom 101 | 10 Beginner Tips for Entering the Wedding Floral Landscape

- Succession-Planting Flowers | Scheduling & Planning, Sowing Frequency, Record Keeping & Recommendations

- Succession-Planting Interval Chart for Flowers

- Sustainable Floral Design | Techniques & Mechanics for Foam-Free Floristry | Tobey Nelson & Debra Prinzing

- Video: Mason Jar Bouquet Tutorial

- Video: How to Build a Bouquet

- Video: Tobey Nelson | Sustainable Floral Design | Slow Flowers Summit

- Video: Economic Considerations in Overwintering Cut Flowers | Johnny's Selected Seeds

- Top 10 Cut-Flower Varieties for Direct Seeding

- Video: Floating Row Cover | Baby "Cool Flower" Protection from Whipping Winter Winds

- Video: The Procona System for All-in-one Flower Harvest, Transport & Display

- Johnny's Overwinter Flowers Tunnel: Trellising, Supports, Ground Cover & Spacing

- Video: Irrigation Considerations for the Overwinter Flowers Tunnel | Johnny's Selected Seeds

- Video: Johnny's Overwinter Flowers Trial Recap

- Video: Producer Cooperatives for Small-Scale Farmers | Johnny's Webinar Series

- Climate Adaptation for Vegetable & Flower Farmers | Johnny's Educational Webinar Resources

- Webinar Slide Deck | Flower Growing in Southern States | PDF

- Webinar Slide Deck | New-for-2023 Flowers & Floral Supplies | PDF

- Choosing Flower Crops to Overwinter | Guide to Overwintering Flowers

- Forcing Tulip Bulbs | Guide to Forcing Flower Bulbs

- Chrysal Clear Bulb T-Bag | Cut-Flower Conditioner | SDS

- Bloom to Boom: Flower Farm Profitability

- Webinar Slide Deck | U-Pick Power for Your Flower Farm | PDF

- Chrysal Professional 1 Hydration Solution | SDS

- Floral Standards for Flower Farm Collectives and Cooperatives

- Chrysal Professional 2 Transport & Display T-Bag | SDS

- Eat Your Flowers: Serve Up That Wow Factor With Edible Flowers

- Snapdragon Groups Explained

- When to Start Seeds for Overwintered Flowers | Guide to Overwintering Flowers

- Introduction to Forcing Flower Bulbs in Soil | Guide to Forcing Flower Bulbs

- U-Pick Power for Your Flower Farm | Johnny's Webinar Series

- Flower Growing in Southern States | Johnny's Educational Webinar Series

- Chrysal CVBN Flower Conditioner | SDS

- Video: Flower Growing in Southern States | Johnny's Webinar Series

- Chrysal Clear Universal Flower Conditioner | SDS

- Chrysal Clear Bulb Flower Conditioner | SDS

- Choosing Tulip Varieties for Forcing | Guide to Forcing Flower Bulbs

- 10 Tips for Building a Profitable Cut-Flower Business

- Webinar Slide Deck | Growing Snapdragons for Cut Flowers | PDF

- U-Pick Power for Your Flower Farm | Johnny's Webinar Series

- Chrysal Classic Professional 2 Transport & Display (Holding) Solution | SDS

- Edible Flowers List: Top 20 Favorites from the Slow Flowers Community

- Chrysal Professional 3 Vase Solution Powder | SDS

- Flowering in the South: Profiles of 5 flower farmers who cope with temperature, humidity, pest & weed pressure

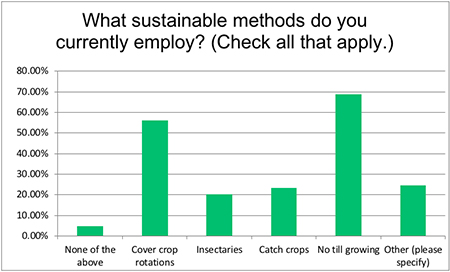

8 Sustainable Farming Methods • A Survey of Flower Farmers' Best Practices

What sustainable methods and techniques do flower farmers employ?

For the past several years, the Slow Flowers Society has surveyed its membership to seek input and responses to a wide array of topics. The insights gained have helped to inform our annual Slow Flowers Floral Insights & Industry Forecast. For 2022, inspired by conversations with Johnny's Selected Seeds' flower experts, we asked survey-takers to share their preferred sustainable farming methods.

Curious about the specifics, I spoke with six of the respondents, who elaborated on their approaches to farming with sustainable methods. These six conversations included Stacey Chapman, of Westwind Flowers in Orange, Virginia; Becky Feasby, of Prairie Girl Flowers in Calgary, Alberta; David Brunton, of Right Field Farm in Millersville, Maryland; Susan Schultze, of Joy de Fleur Flower Farm in St. Paul, Minnesota; Jennifer McClendon, of JenniFlora Farm in Sebastopol, California; and Stacey Denton, of Flora Farm & Design Studio in Williams, Oregon.

Each of these growers has a different story, with farm location, size, and scale and crop specialties varying widely. I learned so much from my conversations with each of these flower farmers, who are all very thoughtful about what they do on their land, as well as articulate about the "why" of what they practice.

The scholar in our ranks is Becky Feasby of aptly-named Prairie Girl Flowers, who grows on less than one acre during Calgary's short growing season in the Canadian Prairie region. She advocates for sustainable growing and design practices through her popular Sustainability Sunday series on Instagram and is a Master's candidate in Sustainability at Harvard University, researching ways the floral industry can change to eliminate the use of chemicals and plastics.

"We need to study preindustrial farming," Feasby maintains. "When you look at the way indigenous peoples have farmed — and do still — that's the way we could all be doing it. It's just that we've moved away from those methods," says Feasby, "largely for the sake of convenience and because so many products have been pushed on us by manufacturers." Many flower farmers and farmer-florists, however, "are doing a pretty good job," she says, "if for no other reason than the bulk of us are fairly small scale."

Defining Terms

Photo: Nikki Collette Photos

There's a whole living language around the term sustainable agriculture. Popular terms like this tend to be open to interpretation, and can be used and also misused. Likewise, the terms regenerative agriculture and indigenous agriculture can be defined in a variety of ways.

The commonalities among them, however, are more important than the differences: they encompass practices that are now helping to advance and define just what is sustainable in agriculture, as well as, more broadly, in land stewardship.

These practices may include organic agriculture, agroforestry, fish farming, crop rotation, fallowing, intercropping, polyculture, permaculture, water harvesting, and many others. Because this is not a scientific report but a survey article, however, we will include a few general definitions as we cover our survey conversations, and for those who want to learn more we have listed our references at the bottom of this story, along with some recommended further reading.

Catch Crops & Cover Crops on Flower Farms

A cover crop is one that is planted to suppress weeds and to build and preserve the soil without the use of chemical fertilizers and herbicides. They are usually planted in-between one cash crop that has been harvested and terminated and a subsequent one not yet sown.

Cover crops tend to be annuals — crimson clover, winter rye, winter barley, spring barley, spring oats, buckwheat, foxtail millet, pearl millet, fava beans, black oats, hairy vetch, field peas, and winter wheat — but can also be perennials, such as red clover and sunn hemp, that can be grown as either one or the other, depending on the latitude.

Many growers find the best success with those that quickly become established, to prevent soil from eroding and weeds from predominating, but which can also be terminated readily and at the right time, to suit the grower's purposes.

Depending on the type of cover crop, other benefits can include adding organic matter to the soil; sequestering soil nutrients; preventing existing nutrients from leaching out of the topsoil; supporting soil organisms in the root zone; and providing habitat for aboveground beneficial organisms.

Leguminous cover crops add nitrogen to the soil when they are terminated and returned to the soil, and are therefore often referred to as green manure crops. Cover crops are also sometimes referred to as catch crops because they can take up and retain nutrients that might otherwise leach from the rooting zone and be lost to deeper soil profiles, and potentially to groundwater.

David and Lina Brunton of Right Field Farm grow, design, and deliver a mix of perennial and annual flowers with an eye toward all the natural beauty their corner of Maryland offers. From April to October they deliver abundant, garden-inspired, hand-tied arrangements featuring over 200 varieties of flowers. According to David Brunton, the farm benefits from a rotation of two main cover crops: a "hot season" planting of buckwheat (which, he says, "is not actually a grain but a relative of rhubarb") and a "cool season" planting of winter rye.

"Two years ago in our business plan," says David, "we set the goal of eliminating bare ground so that all soil has something growing in it. It's nice to have something growing that specifically suppresses weeds, builds soil health, attracts pollinators, and creates green manure."

He lists many benefits of buckwheat, including the bonus that it's a pretty cut flower for bouquet design: "I've never seen anything that attracts as wide a variety and as large a number of pollinators as buckwheat blooms. It is not a nitrogen fixer, but it does contribute to the overall health of the soil." The winter rye scavenges residual soil nitrogen and goes into rotation with flower crops that are heavy feeders, including zinnias and dahlias.

At Westwind Flowers, Stacey Chapman is a third-year flower farmer who grows on one acre and sells at farmers' markets, through CSA and flower share programs, and wholesale through Old Dominion Flower Cooperative (highlighted in our story on regional wholesale flower hubs). She and her husband Tom Chapman lease two acres of land from the Montpelier Foundation, the historic James Madison farm outside of Charlottesville, where they primarily raise field-grown flowers. "We are very aware of sustainability and what that means here," she says. "If we ever leave this land, we want to leave it in better condition than we received it."

Photo courtesy of Westwind Flowers

Prior to Westwind Flowers being established there in 2019, the farmland had been used for horse grazing for nearly a century, and later planted in cover crops to attract natural pollinators, Chapman explains. "We have divided one acre into 50x50-foot blocks; and those blocks are divided into beds. Two of our new open blocks that will be cultivated this year are currently under red clover. It's a great way to build up the soil health and nutrition, and to improve its viability. We will till that in and build our beds from there this spring. Later, we will plant a cover crop of buckwheat in beds that we know are done for the season and don't have a second crop in rotation. Once the buckwheat is done, we will cover it to terminate it or let it winter kill."

Susan Schultze of Joy de Fleur is a wedding and event florist and container designer based in the Twin Cities. She grows cut flowers on family acreage located about 2 hours away in Southern Minnesota. Schultze came to flower farming a few years ago, planting about half an acre of flowers such as zinnias, snapdragons, celosia, cosmos, amaranth, and dahlias to supply her design studio. She uses landscape fabric for the flower rows, which are arranged on gently sloping land. "It's slightly terraced, and each row has a slight elevation difference. For that reason, we planted white clover between the rows, both as a pathway material and to put nitrogen into the soil."

Insectaries, Beneficial Insects & Pollinator Habitat

Insectary plants are used to attract and sustain beneficial insects as a means of biological pest control. These plants provide food in the form of nectar and pollen, which the adult forms of many beneficials, such as predatory and parasitic insects, require for completion of their life cycles. Insectary plants can also host organisms that serve as alternative foodstuff for the predatory insects, which helps to keep the colonies of the predators abundant locally. Insectary plants thereby increase the numbers and effectiveness of natural enemies that help suppress pest populations. Another ecosystem service they provide is habitat and sustenance for pollinator species such as bees, wasps, birds, and beetles.

Photo courtesy of Joy de Fleur Farm

Jennifer McClendon of JenniFlora Farm is a small-scale grower in Sonoma County's wine-producing region, which also happens to be a popular wedding destination. She has shifted the focus of her production almost entirely to 1500 garden roses that supply area florists as well as her own design work. As part of her farm's sustainability focus, McClendon has cultivated a hedgerow border with woody ornamentals such as abelia, spirea, ninebark, and lavender — "things the bees love," she says, noting that the flowering perennials and shrubs are equally useful to supplement floral designs.

Committed to tending the thriving ecology that their farm supports, Right Field Farm doesn't use any pesticide inputs — not on their flowers or in their soil. "I consider our whole farm an insectary," Brunton points out. "Having cultivated this habitat for a long time, I recognize that one of the things that naturally occurs is lots and lots of insects, some of which are pests. I think of our bumper crop of chamomile that blooms each spring, and every single year we see aphids on the new growth. The first thing I do is just freak out a little bit, squeeze a few of them with my fingers, then realize I'm never going to stay ahead of them. If I wait and do nothing, about a week later the green lacewings and the ladybugs show up, and even some of the larger predators, a mantis or a wasp, to take care of the problem. If I were to spray even with an organic insecticide, it could knock back the predators worse than it knocks back the pest insects." His point: Letting Mother Nature take care of things is a lesson learned through observation and patience.

Stacey Denton of Flora Farm & Design Studio in Oregon's Applegate Valley, is currently going through the process of becoming a certified organic farm through Oregon Tilth. "I want to differentiate myself in my market, and having the certification is a commitment that has accountability behind it."

She considers the two-acre native forest on her property a resource for foraging and also for habitat. "A lot of my margin is planted with a 'shelter belt' — trees, shrubs, and understory plants. I have species that include lilac, forsythia, Japanese quince, and willow, which I also gather from. The term shelter belt refers to a planting similar to a hedgerow, " Denton explains. "It provides the niches where animals like birds, reptiles, and insects have habitat, forage, and interact with other species. It's a critical part of my organic management because it provides those things in the off seasons, when things aren't otherwise blooming in the fields, like my annual crops. The shelter-belt perennials and biennials are helping to maintain the ecological balance on the farm."

Growing Flowers Using No-Till & Low-Till

No-till practices reduce erosion, conserve and build soil organic matter, and increase soil biological activity. Existing soil structures remains intact, protecting and helping to "mature" the soil profile by leaving crop residue and other detritus at the soil surface. Improved soil structure and soil cover help growers manage moisture by increasing the soil's ability to absorb and filter water, which in turn reduces erosion and runoff, which prevents pollution from entering the watershed. No-till practices also slow the rate of evaporation, allowing for better absorption of precipitation as well as irrigation efficiency, all of which leads to higher yields, especially during hot or dry spells.

Stacey Chapman practices "limited tilling," which in her operation means that the first time cover crops are used in a planting bed, they are tilled in. "Then the bed becomes permanent and we just continue to add on top of it, whether it's compost, leaves, mulch or straw." She adds that the farm's name "Westwind" is a true reflection the site's exposure to the elements. "The wind blows from the west out here and there are no buffers, so having our soil covered in some way is extremely important."

Photo courtesy of JenniFlora Farm

According to Feasby, "No-till is definitely gaining footing among flower farmers here in Canada, and the reason behind it is the carbon crisis that is causing climate change. When you till the soil, it releases carbon. There's a lot of pressure on agriculture to change. Some of the problems relate to conventional cattle ranching methods, but a lot come from disturbing the soil. When you dig up and stir the soil, especially on a large scale, you release a lot of carbon into the atmosphere." She advocates using a pitchfork or broadfork to minimally prepare the soil by hand for new plantings. "I try to disturb the soil as little as possible and I amend with compost from a local supplier," she explains. "It's a bit of a brain-disconnect to realize that by tilling some soil, you're harming the planet," she observes. "It's easy to see how carbon is released into the atmosphere when you drive your car, because there's exhaust pouring out the back, right? But when you till the soil, it's not normally a negative visual."

Not using mechanical tilling methods is one way to mitigate carbon release, but tactics like cover crop planting also help by sequestering carbon, Feasby points out. "People here are also moving away from using peat in any form in their soil-blocking and in potting soil mixes. Because peat bogs are these amazing carbon sinks, they hold a ton of carbon in the earth. And at this point in the climate crisis, we need to be holding on to as much carbon as we can and to be willing to reduce our carbon emissions. So that means leaving peat bogs alone."

Right Field Farm's Brunton considers its perennial plantings, which now comprise about 60% of their flower mix, to be part of the farm's no-till practice. He's also experimenting with occultation. "We lay landscape fabric over a 15x40-foot bed and anchor it with sandbags. The warmth that accumulates causes the seeds beneath it to germinate more rapidly and more effectively, but then they don't have any sunlight so they die, and that reduces the weed pressure in those plots over time." The decrease in the weed seed bank in that topsoil means crops planted subsequently without tillage will in turn require far less soil disturbance in the form of cultivation to clear weeds.

Photo courtesy of Flora Farm & Design Studio

What other sustainable methods do flower farmers use?

Here is a snapshot of several other methods cited by our survey respondents as essential to their farm's sustainability. We don't have room for all the details and actionable examples of the many responses, so we'll touch down on a few areas you can delve into further as your interests and sustainability needs and priorities dictate.

Generating On-Farm Biological & Mineral Amendments

Soil amendments generated on-farm or shared between neighboring farms can include green manure, manure, and litter from animal husbandry. These are all sources of organic matter as well as major mineral nutrient sources after mineralization. Because soil fertility governs the plant productity of the soil, these organic, low-input types of amendments can play a critical role in long-term productivity.

Denton employs many of the sustainable practices touched on here, and she is experimenting with some other, newer ideas for her four-acre homestead. "I'm doing my best to limit how much bagged and imported mineral and biological amendments are coming onto the farm, in part because I then begin to depend on them. If I have to buy those products to create fertility on the farm, likely from a source nowhere near my local bioregion (perhaps even transported across the ocean), it also leaves a much bigger carbon footprint."

Denton wants to increase on-farm production of her own biological and mineral amendments. "What can we create for ourselves rather than buy at a store?" she asks. It can be something as simple as making a vinegar extraction of calcium from eggshells, for example, which she currently employs.

Denton is also eager to cultivate her farm's indigenous microorganisms to boost the bioactivity of compost and field soil. Application of the cultures as a top-dressing to crop soils can potentially enhance plant-beneficial soil microorganism activity, minimizing the need for applications of inorganic soil amendments while improving soil structure and plant health. Common for centuries on farms in the East and Africa, the practice itself of collecting and applying innate "good" microbes is simple, practical, reliable, and economical. But the science underpinning IMO-based (indigenous microrganism-based) technology is far-reaching, complex, and still emerging here in the West — though introduced as far back as 1960. Today, indigenous soil species are being researched and hold promise not just as sustainable sources of biofertilizer but as a means to mitigate and even undo environmental distress.

Reducing or Eliminating the Farm's Reliance on Plastic

There are many and varied ways that flower farmers can help to reduce their use of plastic on farm. We could not cover them all here, but do discuss discuss one aspect of our industry's overdependence upon plastics in Sustainable Floral Design: Techniques & Mechanics for Foam-Free Floristry.

As often as we may have heard it over the years, it bears repeating that among practical folk the simple directive to "Reduce, Reuse & Recycle" will never fall on deaf ears. Feasby is vocal about reversing the floral industry's reliance on plastics for so many applications. "Some plastics applications are single-use and some are durable goods. I have plastic trays that are 10 years old for growing my seedlings, so I consider that durable. But we have to get away from throw-away plastics. Think of a potting soil package or the flimsy six-packs that pansy and other starts might come in. A lot of the plastic sheeting isn't super long-lasting, either. Those are not durable goods."

Before we reach a target of zero waste, however, we will still have plastic waste to store on the farm, transport, or arrange for its disposal. For this there is no single solution for everyone, so it's essential for us all to do our research and shop around for the best goods, services, and prices to fit our needs and sustainability goals.

Foliar Feeding with Plant Ferments & Emulsions

Similar to using indigenous organisms, another form of inexpensive, homemade additive is a versatile mixture known as a fermented plant extract. The basic process generally used involves adding lactic acid bacteria and a form of sugar to chopped-up plant materials. The fermentation process breaks the plants down and the liquid is then left to rest. After a time the nutrient- and microbe-rich liquid serum can be siphoned off and added to irrigation water, applied directly to the root zone, or used as a foliar spray. Other plant ferment applications include using them as compost additives to accelerate decomposition, or as top or side dressings to crops.

While not certified organic, McClendon uses organic practices and sustainable methods. "Roses are my own passion and also what the market demands, but I also grow some annuals such as sweet peas, and perennials such as thornless raspberry and dahlias." Sustainable rose treatments include foliar sprays made from kelp and fish emulsions. "I only buy OMRI-certified amendments locally, and then I mix them up and fill my backpack sprayer to apply. The extra organic material encourages healthy growth so that my roses, hopefully, can fight off disease naturally."

Heavy Mulching

We cannot overstress the many benefits of mulching, as noted in relation to mitigating the effects of heat and drought in How Flower Farmers Are Adapting to Changing & Challenging Climatic Conditions. As a critical component of regenerative agriculture, mulching also bears mention in this article.

At Joy de Fleur in southern Minnesota, the 30-acre family land is part of a certified tree farm and bee habitat. The bees, trees, and flowers are working together as an agroforestry unit that forms part of a larger soil and water conservation initiative for marginal farmland. "We worked with the state to put in plantings of red pine trees as wildlife habitat and white pine trees as a crop. "I started using pine needle mulch because, one, it's available and easy to use," says Schultze. "Second, even here in Minnesota, our weather has been wild the last couple years, with temperatures ranging from a super-hard, late frost in May that quickly spiked to 100°F (37.8°C). Sometimes it gets so hot, so early in the season, that I worry the heat near the surface of the black landscape fabric will destroy my seedlings. I start layering the pine needle mulch around the plants when they are young to moderate the heat and cool the surface temperature of the landscape cloth."

Schultze isn't ready to give up on using the black landscape cloth, though, because it does help to stabilize her terraced beds and protect them from soil runoff. "I bought the type with the highest life expectancy, so I can keep re-using it."

When McClendon was starting out she read books on permaculture such as Gaia's Garden, to learn ways to farm sustainably. "I never really have to worry about weeds because I mulch the pathways with cardboard and then straw, and then wood chips," she says. "That creates a thick layer of mulch, which breaks down, enriches the soil, and acts as a great weed blocker."

Since McClendon picks up loads of free cardboard boxes from a local store, she considers cardboard mulching an economical alternative to plastic ground covers. "This land was a cow pasture before we started JenniFlora," she explains. "Healthy plants begin from the soil up, and over the years, I've seen a huge difference from our practices. Now, there is tons of soil life and the organic matter has increased — and I think it results from keeping the soil covered with mulch."

Learn More

There were many other habitual and sustainable practices cited by survey respondents — measures such as annual soil testing, crop rotation, and brownfield flower farming, just for starters — and we want to acknowledge that together all of them, with all of us, play a role in helping to create a better future for living beings. We are curious to hear what practices you've incorporated into your flower farm — send us your ideas for future topics to cover in this series.

Below, you will find links to related articles in Johnny's Grower's Library and to a few external references. To paraphrase poet Seamus Heaney, we would encourage you on your path to sustainability by "[g]etting started, keeping going, getting started again."

Resources from Johnny's Grower's Library

- Buckwheat : A Quick, Easy Summer Insectary & Weed-Control Cover Crop • Article

- Intro to Farmscaping: Insectary, Trap, & Repellent Crops for Pest Management • Article

- The Pollinator Issue • Article

References

- Perroni, E. 2017. Five indigenous farming practices enhancing food security. Food Tank. (accessed 03.01.2022).

- Heim, T. 2020. The indigenous origins of regenerative agriculture. National Farmers' Union (accessed 03.01.2022).

- University of California Integrated Pest Management Program. Insectary plants. (accessed 03.01.2022).

- Kumar, B.L. & DVR Sai Gopal. 2015. Effective role of indigenous microorganisms for sustainable environment. 3 Biotech, 5 (6), 867–876 (accessed 03.04.2022).

- Nin, Y, et al. On-farm-produced organic amendments on maintaining and enhancing soil fertility and nitrogen availability in organic or low input agriculture. In Organic Fertilizers. M.L. Larramendy & S. Soloneski, eds. (accessed 03.04.2022).

- Park, H. & M. W. DuPonte. 2008. How to cultivate indigenous microorganisms. Honolulu (HI): University of Hawaii. Biotechnology; BIO-9 (accessed 03.04.2022).

- Spears, S. 2018. What is no-till farming? Regeneration International (accessed 03.01.2022).

- Tanner, J. 2022. Brownfield flower farms. Growing for Market, 31 (3), 1–6 (accessed 03.01.2022).

Further Reading

- Dhandapani, N., et al. 2016. Insectaries. In: Ecofriendly Pest Management for Food Security, 311–327 (accessed 01.31.2022).

- Phillpot, S. 2013. Trap crop. Encyclopedia of Biodiversity (Second Edition), 373–385 (accessed 01.31.2022).

- Smith, H.A., & McSorley, R. 2000. Intercropping and pest management: A review of major concepts. Am. Ent., 46 (3), 154–161 (accessed 01.31.2022).

- Liburd, O.E. & Smith, H.A. 2018. Intercropping, crop diversity and pest management. IFAS/UFL (accessed 01.31.2022).

- LaRose, J. & Myers, R. 2019. Impact of cover crops on natural enemies and pests. SARE (accessed 01.31.2022).

- Mohler, C.L. & Johnson, S.E. 2009. Using trap crops to reduce pests. In: Crop Rotation on Organic Farms (accessed 01.31.2022).

- Mohler, C.L. & Johnson, S.E. 2009. How intercrops affect populations of beneficial parasitoids and pest predators. In: Crop Rotation on Organic Farms (accessed 01.31.2022).

- No-Till Growers channel. Building No-Till Soil for Flower Production | Wylde Flowers (accessed 06.15.2021).